In its continuing coverage of the DNO/KRG/Galbraith nexus in Iraq, the Norwegian business daily Dagens Næringsliv has landed a rare interview with the ruler of Iraq in the CPA era from 2003 to 2004, Ambassador L. Paul Bremer. In the interview, published in the hard-copy of the paper on 20 and 21 November, Bremer reflects on Peter Galbraith’s many simultaneous roles in Iraq in 2004, and in particular comments on sovereignty issues related to the signing of DNO’s contract with the KRG.

Bremer – who to a considerable extent has been out of the limelight since he left Iraq and who informs DN that he is currently spending much time pursuing his favourite pastime of painting landscapes – dismisses Galbraith’s pursuits in Iraq as “unethical” and adds that he himself was personally subjected to a two-year ban on business activity in Iraq subsequent to his tenure at the CPA. This characterisation of Galbraith by Bremer is perhaps not terribly surprising given the well-known personal enmity between the two men, and many observers will probably also want to emphasise the multiple ethical questions that pertain to the CPA itself under Bremer’s own leadership and indeed his whole program of using ethno-sectarian quotas as the key for shaping institutions of government in the “new Iraq”. As far as ethics are concerned, what is now happening in the US mainstream media is actually a lot more interesting than what Bremer thinks about Galbraith: An increasing number of leading intellectual forums in the US that used to support Galbraith – including the mighty New York Review of Books – are now following the lead of the NYT in issuing various forms of apologies to their readers for having given space in their columns for Galbraith without at the same time providing full disclosure of his business involvement in Iraq. Conversely, his remaining support base seems to be growing distinctly rural in outlook, and now appears to be limited to angry letters in his defence printed in publications like the Rutland Herald and the Brattleboro Reformer, both based in his home state of Vermont.

Beyond the ethical, the main focus of the DN articles concerns an interesting question about the timing of the contract that was entered into between KRG and DNO back in June 2004. DNO has repeatedly emphasised 30 June 2004 as a key point in time in all their calculations about the legality of their contract in Iraq – the logic being that a contract signed before the transfer of sovereignty to Iraqi leaders on that date would supposedly enjoy a special status in a legal vacuum and therefore be immune against challenges by future Iraqi governments. Apparently in conformity with this logic, DNO notified the Oslo Stock Exchange about its contract with the Kurds on 29 June 2004, and Galbraith’s Porcupine company reportedly came into existence on 30 June. The DN article cites DNO boss Helge Eide with regard to the influence of both Galbraith and the KRG in pushing for a pre-handover contract, clearly showing how the basic intention of everyone involved was to circumvent Iraqi sovereignty.

The problem raised by DN in the interview with Bremer concerns the unexpected change to the date for the handover in Iraq from 30 to 28 June 2004, which at the time was something of a security-related top secret that few others than Bremer and his leading officials knew about. Of course, as Bremer also hints at in the interview, since the transfer of power took place two days early, any sovereignty-focused logic pegged to the expected 30 June date would be at risk once that date was abruptly changed. “We did not tell anyone”, Bremer says in the interview, referring to his agreement with Bush to leave Iraq on 28 June to avoid potential terrorist problems. His description of this is consonant with the account provided on pp. 145–46 of Galbraith’s own book The End of Iraq, which portrays Bremer’s early departure as something that caught everyone by surprise. The implication, of course, is that in theory there could be a problem with the date of the DNO contract, since many of the available documents suggest that it had been planned for a 29 June signature, one day after what eventually turned out to be the actual handover date.

Ultimately, these questions are of greater historical than practical significance. True, it is indeed somewhat conspicuous that DNO has retained 30 June 2004 as such an important feature of its argument to defends the legality of its Iraq operations, and apparently the first reference to the exact date of their contract was only communicated publicly as late as in January 2006 – some 18 months after it came into existence. However, at that point it was given as 25 June 2004, hence before 28 June. Regardless of speculation as to what the actual chronology may have been, it seems safe to assume that documents compatible with that narrative exist, and it would be very hard for anyone to question the real date of the DNO contract in a legal challenge. Additionally, as it turned out, the date for the handover ended up being without any significance whatsoever in Iraq’s 2005 constitution: The only distinction in that document is between contracts signed by the Kurdistan authorities after 1992 and the entry into force of the new Iraqi constitution, which technically did not take place until the seating of the Maliki government in May 2006. If the Iraqi governments under Ayad Allawi and Ibrahim al-Jaafari ever had a theoretical window in 2004 and 2005 for challenging the deal they simply did not use it.

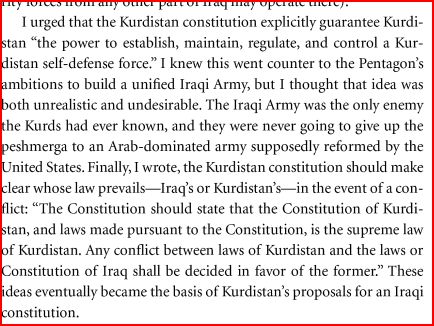

The real problems with DNO’s contract in Iraq are of a different nature than those discussed by Bremer in the DN interview. Above all, they are concentrated in the last section of the very article of the Iraqi constitution – 141 – that is so often evoked by DNO itself in defence of its own position: Pre-2006 unilateral deals by the KRG are valid … “unless they are in conflict with the constitution”. However, while that last part is pretty momentous it keeps getting ignored by DNO. Even if so-called “future oil fields” are not enumerated among the exclusive prerogatives of the central government, a shared responsibility for the entire oil sector is explicitly acknowledged in article 112, and it is hard to see how the bilateral deal between the KRG and DNO can satisfy that criterion for constitutionality unless the DNO contract is submitted to Baghdad for review and consultation. Similarly, the constitutional article (111) on oil and gas ownership stipulates that the oil and gas belongs to “all the Iraqi people, in all regions and governorates”. Again, a production sharing arrangement in which the foreign company holds the right to a substantial share of the oil exported (reported by some sources as high as at 55%) is likely to come under special scrutiny. But above all, it needs to be pointed out that DNO cannot know whether its Kurdistan contract is constitutional. That is simply because the authority for reviewing constitutionality on these matters does not rest with the KRG, DNO, or, for that matter, this blogger! There simply is no point in having huge teams of international lawyers pontificating about the constitutionality or otherwise of the DNO contract, because in any event the final arbiter is going to be someone else – either the Iraqi federal supreme court (in a legal way) or the Iraqi government (in a practical compromise). In other words, all that is certain is that there is uncertainty here. Additionally, of course, there remains the revision clause of the constitution (142) which means that everything in it – including the legality of pre-2006 contracts – can be struck down during the first round of revisions. So far, at least, the tendency in the constitutional revision committee has been towards greater centralised control of the oil sector.

In sum then, the whole idea of a strictly legalistic approach to the DNO contract is of limited value. Legalism may perhaps appeal to someone like Peter Galbraith: Just like Bremer who can go back to painting landscapes, Galbraith can abscond to gubernatorial ambitions in Vermont and enter a multi-million lawsuit against DNO in London. Around the world, there will always be takers for his simple message of ethnic decentralisation as the universal tool for solving political conflict. But left with a difficult situation on the ground are first and foremost the Iraqis, including, importantly, the Kurds – and in this case also DNO and its shareholders. However, what the Kurds and DNO fail to realise is the extent to which the Galbraith legacy has created problems and not solutions for them. Recently, however, this has clarified a good deal as a consequence of Galbraith’s public comments subsequent to the first revelation of his “business interest” in the Tawke oilfield last month, and in particular through his emphasis of the assumed “congruence” of his actions. For example, according to the Vermont newspaper Rutland Herald on 13 November, at a recent public meeting “Galbraith said he had always been supportive of Kurdistan’s self-determination, which meant having control over its oil fields and establishing a Kurdish oil industry.” In cruder terms, oil contracts such as that entered into with DNO could do service as dynamite in a greater vision of Kurdish independence, something which in turn would be “congruent” with Galbraith’s advice and support to the Kurds to seek a maximum of regional power in the 2005 constitution as a prelude to independence. The problem for the KRG and the DNO is that because Galbraith’s prediction in 2006 of “the end of Iraq” failed to materialise, they are now left to pick up the pieces after what amounts to an aborted separatist attempt.

Galbraith’s whole “independence train” for the Kurds was predicated on an incremental tendency of symmetric territorial and political fragmentation in Iraq that just failed to happen. In early 2008 that process stopped as Iraqi Shiites began emphasising their Iraqi nationalism, and ever since Galbraith’s commentary and description of Iraqi affairs have grown increasingly fictitious and irrelevant. So too, of course, have the separatist policies that he supported and helped shape. Accordingly, instead of taking their cues from Galbraith (who is now presumably basking in perfect “congruence” in Townshend, Vermont) both the Kurds and DNO would stand to gain a lot from adjusting their policies to the new realities in Baghdad. Above all, this would mean realising that Iraqi Shiites are not particularly interested in symmetrical federalism for Iraq. True, there are Shiite sectarians today, just like there were anti-Shiite bigots during the Baath. But the irreducible minimum on which all parties south of Kurdistan can agree (and something which an alarming number of Western analysts still just cannot seem to get their head around) is a consensus position on Iraq as a unified territorial shell. Today, the real tension in the Shiite Islamist camp is between Shiite chauvinists who pay lip service to the idea of Iraqi nationalism and Shiites who are genuine Iraqi nationalists – and not so much between centralists and separatists (even ISCI now seems to have given up its federalism ambitions, if perhaps somewhat reluctantly). And so accordingly, Shiites will continue to speak in the name of a unified Iraq, hesitate with regard to the formal enshrinement of sectarian identity in the state structure, and stand up for Kirkuk as a multi-ethnic city attached to the central government in Baghdad, and so on. Importantly – and particularly relevant in view of the apparent revival of friendship between the Kurds and Shiite Islamist parliamentarians lately – even during the heyday of Kurdish-Shiite cooperation back in early 2007, that alliance broke down precisely over the question of the oil law and the Kurdish insistence on an exclusive right to sign foreign contracts. Accordingly, in terms of oil policy, it makes sense for Shiite Islamists to focus on boosting production in the supergiant oil fields in the far south where the true potential is (as testified to by the international oil giants lining up to sign technical service contracts there), rather than making painful concessions related to controversial production sharing deals for the comparatively small fields in the north, including those that involve DNO. When Shahristani gets summoned to parliament this should be interpreted as a failure of his tactics in handling the ministry rather than an end to the overall strategy of putting the south first; in fact some of his current detractors in parliament (such as Fadila) are even more vehemently opposed than Shahristani to the whole concept of production-sharing deals with foreigners and independent Kurdish decision-making on oil.

In sum, while the Bremer interview in DN raises many important questions (one that is not answered is whether Bremer actually had the authority to stop the DNO deal if in fact the agreement was entered into during the CPA reign), perhaps both the Kurds and DNO would obtain better results today if they tried to revisit Kurdish aims as defined prior to the arrival of Galbraith, Bremer and the whole CPA. For example, back in 2003, the Kurdish draft constitution for Iraq actually defined a bi-national Arab-Kurdish federation in Iraq in which Baghdad controlled the oil sector. Hence, instead of hinting about suing Baghdad over lost income from oil exports in the summer of 2009 (likely to prove a non-starter in negotiations with the oil ministry and something that will only increase the anger of Iraqis who are already infuriated by Galbraith’s multiple roles in contributing to the design of both the DNO contract and the constitutional framework that governs it), at some point in 2010 after the parliamentary elections when a new Iraqi government has been formed the KRG and DNO could try to enter into negotiations with Baghdad about converting their current agreement to a service contract more acceptable to the Iraqi public – a solution that reportedly would still be pretty lucrative for everyone involved and therfore a win-win situation. Many Iraqis south of Kurdistan are hoping that the new KRG government headed by Barham Salih will prove a lot more moderate than the previous one, and that the old scheme of a unified Iraq with a special status for Kurdistan can once more come to the fore as a sustainable political arrangement. Conversely, in their own visions for Iraq, both Bremer and Galbraith ultimately proved themselves to be out of touch with the dominant trends of the country’s politics.