Whereas the IHEC press conference announcing the results of Iraq’s 20 April local elections was merely a readout of the names of the winning candidates and their political affiliations, a second batch of useful information, giving the numbers achieved by each candidate, has now been published. This material makes it possible to analyse how the Iraqi electorate uses the “personal vote” option, whereby voters alongside their vote for a particular political entity can indicate their candidate of choice on that slate. When the votes are counted, the pre-set ranking of the candidates done by the party leadership is ignored altogether, and only specific personal votes garnered in the election count as the ordering of candidates on a particular list is done all over again.

Before discussing patterns of electoral behavior, some basic information about how the ballots are cast in an Iraqi election can be useful.Technically speaking, Iraqi voters do not actually receive ballot papers that include the names of the candidates, only the entity names and numbers. Accordingly, in order to make use of the personal vote option, they need to know the number of their preferred candidate and then fill in that candidate’s number after they have checked the box for their party vote. In theory this can happen in two ways: Either by knowing the candidate’s number beforehand (and remembering it at the voting booth), or by checking a register of all candidates available at the polling station. In practice, most personal votes are probably the result of beforehand knowledge. Electoral propaganda for individual candidates almost invariably includes the key two numbers that voters require, i.e. party list number and candidate number.

Typical Iraqi election poster showing political entity (419) and candidate number (2)

Then, to the actual use of the personal vote in the 20 April 2013 provincial elections. The first point that is worth making is that the personal vote option is indeed being used by the electorate – a lot. The following quick calculations are meant to provide a cross-section of contexts and electorates and show that across parties and governorates, from Iraqiyya to Shiite Islamists and from rural Maysan to the capital Baghdad, a large majority of Iraqi voters indicate their preferred candidate when they vote. Most of the examples indicate above 90% use of the candidate vote, and nowhere is the percentage less than 84%:

|

Hakim list |

Maliki list |

Nujayfi list |

Sadr list |

Iraqiyya |

| Basra |

|

91.5% |

|

|

|

| Muthanna |

98.2% |

97.3% |

|

|

|

| Wasit |

89.7% |

93.6% |

|

|

|

| Baghdad |

|

|

84.1% |

84.3% |

|

| Salahaddin |

|

|

97.6% |

|

98.9% |

*

As for the individual results, the following is a list of Iraq’s 15 most popular provincial politicians, indicating personal votes achieved, list and position on list:

1 Khalaf Abd al-Samad 130,862 Basra 419 1 (Basra governor)

2 Salah Salim Abd al-Razzaq 68,895 Baghdad 419 1 (Baghdad governor)

3 Umar Aziz Hussein Salman al-Humayri 52,219 Diyala 458 58 (Diyala governor)

4 Adnan Abad Khudayr 41,006 Najaf 441 1 (Najaf governor)

5 Ali Dayi Lazim 38,605 Maysan 473 1 (Maysan governor)

6 Riyad Nasir Abd al-Razzaq 21,446 Baghdad 444 1

7 Kamil Nasir Sadun al-Zaidi 18,870 Baghdad 419 2 (Baghdad council speaker)

8 Muin al-Kazimi 17,927 Baghdad 419 5 (leading Badr figure)

9 Adil al-Saadi 16,686 Baghdad 419 6 (top candidate Fadila)

10 Muthanna Ali Mahdi 14,225 Diyala 501 3 (Badr)

11 Majid Mahdi Abd al-Abbas 14,147 Basra 411 1

12 Ammar Yusuf Hamud 13,048 Salahaddin 444 1

13 Saad al-Mutallabi 12,604 Baghdad 419 10 (prominent State of Law politician)

14 Muhammad Mahdi al-Saadi 11,502 Diyala 501 1 (Fadila)

15 Ahmad Abd al-Jabbar 11,470 Salahaddin 475 2

Several points are worthy of note here. Firstly, many of these seat winners, especially those with the highest votes, are governors. Presumably, the number one candidates on the various lists have an advantage in terms of the ability of voters to remember who they want to vote for (note though that the Diyala governor humbly put himself at the bottom of his list, only to be promoted to the top with a safe margin by his grateful electorate). But a closer look at the new councils indicate that the personal vote has done more than just provide a bit of symbolic backing for top candidates whose seats were never under threat anyway. Crucially, a very large proportion of the new Iraqi provincial councilors have been promoted through the personal vote results, rising from positions on their party lists where they would not have received seats according to the preset formula decided by party leaderships.

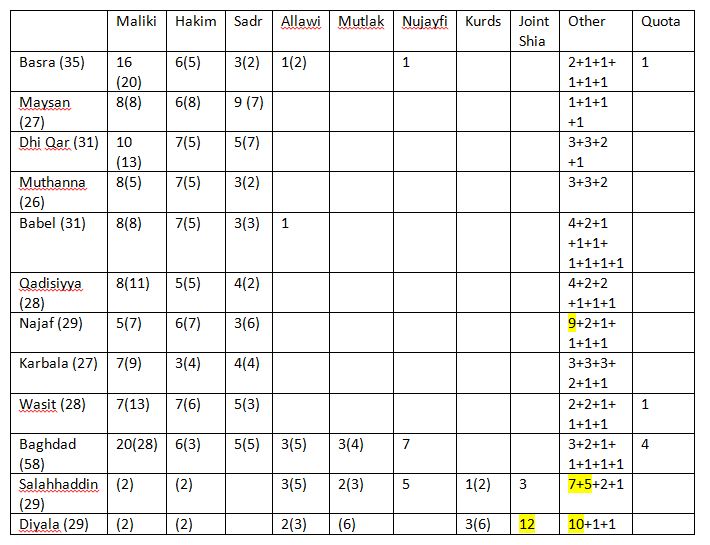

The best measure for seeing the effect of the popular vote is to carefully study that second set of tables issued by IHEC, which ranks candidates strictly after their personal votes. Note how almost all the major lists have very high percentages of candidates that moved forward to high positions due to personal votes they accumulated, mostly with more than 50% of the candidates rising to the top of the lists of vote getters being promoted from positions further down on the list (the main exception being the Sadrist, with somewhat lower rates). This is not the whole story, though. Because of the women’s quota, the eventual seat winners are not strictly the candidates that won the most votes. Given the requirement that every fourth seat goes to a woman – and that women with a few notable exceptions garnered relatively few personal votes – the women’s quota in Iraq effectively continues to serve as a check on the electorate’s will (and as such often tallies with the interests of party leaderships, the obvious advantages of having higher female representation notwithstanding). The following table shows the number of top-candidate councilors who remained in seat-winning positions also after the personal vote had been counted (first number); councilors that were promoted from non-winning positions due to the popular vote (second number); and finally women promoted through quota arrangements (third number). It should be added that there are probably no more than a couple of women in the second group of candidates that were promoted because they outnumbered other candidates (including men) in the personal vote, the best example probably being Aisha al-Masari of the Nujayfi list in Baghdad, who got 11,400 votes and thus almost made it to the national top 15.

|

Hakim list |

Maliki list |

Sadr list |

| Basra |

2-2-2 |

4-8-4 |

2-0-1 |

| Maysan |

1-3-2 |

2-4-2 |

3-3-3 |

| Dhi Qar |

1-4-2 |

3-4-3 |

2-3-0 |

| Muthanna |

2-4-1 |

3-3-2 |

2-0-1 |

| Qadisiyya |

2-2-1 |

2-4-2 |

2-1-1 |

| Babel |

1-4-2 |

3-3-2 |

2-1-1 |

| Najaf |

4-1-1 |

1-3-1 |

2-0-1 |

| Karbala |

2-0-1 |

3-2-2 |

3-0-1 |

| Wasit |

2-3-2 |

2-3-2 |

2-2-1 |

| Baghdad |

2-2-2 |

9-5-6 |

2-2-1 |

*

In sum, the personal vote option, favoured by the Shiite clergy when it was introduced in 2008, remains largely successful in shaking up Iraqi politics. To some extent, the system was ridiculed when the Sadrists used it to the maximum in the parliamentary elections of 2010 by carefully orchestrating large number of personal votes for several Sadrists candidates who could then advance internally within the Iraqi National Alliance at the expense of other entities who saw their personal votes wasted on top candidates or not used at all. Nonetheless, these latest results show that the personal vote is here to stay in Iraq, and that elite politicians who choose to ignore it may be doing so at their own peril.